By Génesis Dávila Santiago and Dashiell Allen

May/2023

A Spanish version of this story was published in El Deadline

A woman with swollen eyes looks up towards the sky. She carries her hands laden with white flowers, and in front of her, is the scene where her husband fell from a bicycle a week earlier while working as a food delivery man.

«Not because we are immigrants are we going to stay in the dark,» exclaims Cristina Ramirez, from the banks of the Hudson River on the Upper West Side, as she raises money with family and friends.

On February 22 of this year, Ramirez was left a widow with three children, no job, and the task of repatriating her husband, Jacobo Villano Pardo, to Mexico, so her in-laws could say goodbye to their 33-year-old son.

«His parents live there … and they want to see their son,» Ramirez explains later from home. «I understand the pain they feel, too, as I am feeling it.»

Ramirez recalls that Villano Pardo wanted to return to live in Tlapa de Comonfort, his hometown in Guerrero, Mexico. «When we were old, we were going to go live in Mexico,» she says. But she never imagined that her husband would return in a coffin.

Cristina Ramirez raises money for the repatriation of Villano Pardo near the banks of the Hudson River. Photo: Dashiell Allen

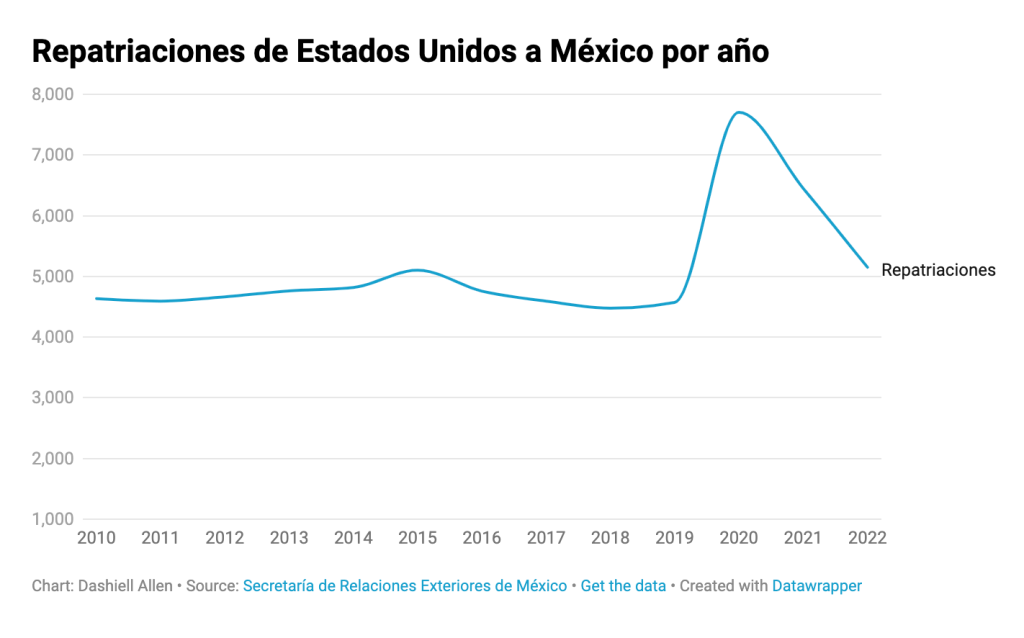

For Ramirez, and for the more than five thousand migrants who transfer the remains of their loved ones from the United States to Mexico every year, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, repatriation has a cost. It fluctuates between $6,000 and $10,000 that migrant families have to pay, often in unexpected ways, and to carry out the procedures with grief on their backs and without previous orientation.

Although repatriation is part of the ideal for many migrant families, according to experts, in New York City, the median income of Latino communities is one of the lowest in the entire population – $47,000 per year, according to Census data. As a result, many families find it difficult to have savings accounts or life insurance.

In addition, Latino populations have one of the highest percentages of premature deaths, 54%, in the state compared to other ethnic groups, according to the Department of Health. Data from the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs indicate that more than half, 56%, of the people repatriated to Mexico from different parts of the world were under 56 years of age.

The Mexican Consulate in New York plays a crucial role in repatriations. In addition to processing documents that identify the deceased and his or her family members so that the body can be transferred to Mexico, in some cases, the Consulate provides financial assistance to cover part of the costs of the process.

However, of the six families interviewed for this report, most highlighted that the Consulate’s services were insufficient because the money granted did not cover the expenses in full and the guidance on the process was not always clear.

A 2017 regulation still in effect states that consulates offer a maximum of $1,800 for purposes of repatriating the remains of a loved one who is a national of the country. Although Ramirez was able to raise the funds for repatriation thanks to financial assistance from the consulate and various donors, not all families receive help.

Regarding the generalized feeling of lack of help from the Consulate, the entity issued a written statement in which it assured that its repatriation program is not based on supporting, in its entirety, all families. «The authorized resources partially cover the cost of the service according to the established norms,» but in exceptional cases, the entity added that they can cover the total cost.

Repatriations per year from the United States to Mexico. Chart by Dashiell Allen

On the other side of the Hudson River, where Ramirez mourns the loss of her husband, Irma Rojas, a resident of New Brunswick, New Jersey, is handling the repatriation of her brother, Orlando Rojas. Lacking a Mexican consulate in her state at the time, Rojas had to travel for an hour to get to the New York Consulate where she alleges she was denied help, for failing to comply with one of its requirements.

«I would ask the Consulate not to ask for so many requirements because you go with pain and ignorance,» Rojas reflected months later. «I didn’t know anything.»

According to Rojas, after her brother’s death, the New Brunswick woman made a contract with a funeral home without knowing that she had to request quotes from three different funeral homes to be considered by the Consulate. In addition, she was unaware of a list of funeral homes preferred by the Consulate, which is only presented to a family when they request assistance.

The Consulate specified, in an unattributed statement, that the request for support on behalf of Rojas’ repatriation was initiated in Mexico City, and not by Rojas. However, they did not explain why she did not receive assistance.

«It is important to note that the individuals’ lack of knowledge of the requirement to submit three quotes to the Consulate General of Mexico in New York is not a reason to deny support,» read the Consulate’s written statement.

Although the Mexican Consulate in New York did not provide this media outlet with the list of funeral homes, press officer Eunice Mirem Rodriguez argued in a written statement that the Consulate «does not have agreements with any funeral home,» but that the list exists to «facilitate obtaining quotes and that people have access to funeral homes that have demonstrated seriousness and efficiency in the services.»

Rodriguez also explained that economic assistance is based on the applicant being in a «situation of poverty or insolvency,» and the amount granted will depend on a questionnaire, an interview, and the consular unit’s budget at the time.

In the absence of help from the Consulate, Rojas turned to her community: she pasted photos of her brother on boxes that she distributed in restaurants she frequented. In addition, Francisco Valentin, a local activist, helped her record a video on Facebook to ask for funds.

«A lot of countrymen who live nearby went and contributed to me,» Rojas says.

«The truth is that the community here in New Jersey is very united,» she says.

A relative of Jacobo Villano Pardo raises money. Photo: Dashiell Allen

For Alejandro Robles, a Mexican migrant deputy based in Toronto, Canada, part of the confusion of the repatriation process is that the consular service is too opaque and bureaucratic.

«If a fellow national is in need of help, it is preferable for him to go to a nonprofit rather than to his consulate because in his consulate he is not going to receive any attention,» Robles laments. «You always have to prove everything. There is never a principle of good faith.»

His point of view is echoed by Adrian Felix, a professor at the University of California at Riverside, whose studies on Mexican repatriations have shown that the repatriation process is often difficult for families on an emotional level due to grief, but also on an institutional and governmental level.

«If there is no information, if there are no resources, if there is no accessible support, of course, it becomes even more complicated [the process],» Felix explains while detailing that communities with long migratory histories in certain regions tend to have better connections with migrant community organizations and consulates that facilitate the process.

The Consulate reiterated in its statement its «availability of contact with the Consulate General and CIAM (Centro de Información y Asistencia a Personas Mexicanas), as well as portals where information on protection services can be found exclusively.»

For Jonathan Juarez, director of the funeral home Previsiones Pedregales del Sur in Mexico City, which receives bodies repatriated from the United States, the difficulty of this process is also due to cultural differences: in Mexico, in many cases, a person is buried one or two days after his or her death. In contrast, repatriation takes weeks to months. That time «can take forever for Mexicans,» he says.

On the banks of the Hudson River in Manhattan, Ramirez paints a bicycle white as a symbol of her husband’s death. She is surrounded by dozens of people collecting money and praying for Villano Pardo’s soul. Among those present is Maria Varela, a Mexican congresswoman based in the Bronx with experience guiding families through the repatriation process.

Varela, who came to New York at the age of fifteen, understands why Mexican families need to repatriate their loved ones in full body. She remembers not being able to travel to Mexico when her father died after not seeing him for more than fifteen years.

«It changes a lot to say ‘I didn’t even see him,’ it leaves a very strong emotional hole in people,» Varela explains.

Families contact Varela, who helps them make videos on Facebook, to ask for financial help. In addition, Varela points out, these videos leave evidence of the difficulties in the repatriation process, which she can use to advocate for change with the Mexican government.

Supporting families with repatriation «makes me feel more sensitive to humanity,» Varela says.

It was through Varela that the family of Modesto Enciso González, from Mexico, distributed a video to raise funds for his repatriation. The 45-year-old man lacked close relatives in New York, and although he had been dead since January 19, his family in Hidalgo, Mexico found out on March 30 through a Facebook post.

«At the time, it was complicated for us, but thanks to God [and] following the indications, we made it,» expresses his sister, Marcelina Enciso Gonzalez, a few days after Mr. Enciso Gonzalez’s repatriation and burial were completed on May 6.

Although this family received $1,000 from the Mexican Consulate in New York and other funds from two Mexican initiatives, the deceased’s son, Gustavo Enciso Gonzalez, said that community fundraising helped him meet the $5,600 goal. Like Rojas, with the help of the deceased’s co-workers, they placed boxes in stores for people to donate.

«We are low-income… it was a little complicated for us to reach the goal of raising the amount needed to repatriate the body,» explains Enciso Gonzalez, who, four months after the death of his brother in Staten Island, says he does not know the cause of death.

For its part, the New York City Chief of Medical Examiner’s office explained in an email that Enciso Gonzalez arrived at the morgue in February after a local hospital notified them that his body had not been claimed. The government agency argued that since it was not in charge of the investigation into the 45-year-old Mexican’s death, it also could not pinpoint his cause of death.

«We didn’t know how, when, or where [he died],» said Ms. Enciso Gonzalez, explaining that due to the decomposition process of the body, she was not allowed to open the coffin to see her brother, who had been in New York for 18 years, for the last time.

During the wake of Villano Pardo, Ramirez’s husband, the coffin also remained closed.

Although many families insist on assuming the costs of repatriating the full body of their relatives, instead of ashes, which are usually cheaper, for various reasons, families are not always able to open the coffin during the wake.

According to Felix, this insistence on transferring the whole body regardless of its condition is due to cultural as well as religious factors, as many Mexican families are Catholic.

«The repatriation of a body is extremely important because of the traditions and rituals after death to give the corpse a Christian burial… Migration complicates even more these processes of mourning and mourning… but it is important to emphasize that many families look for a way to return their loved ones,» explains the academic.

For his part, Osman Balkan, assistant professor at Swarthmore College, points to three main reasons why families choose to repatriate their loved ones: the feeling of belonging to a place and their connection to that place’s past, where the family is in the present, and the discrimination that a migrant may experience in the land they inhabit.

«Among many migrants, there is this idea of the myth of return,» Balkan explains, adding that these dreams are not always fulfilled, and it is after death that family members often decide what to do with the remains of each person.

About a month after Villano Pardo’s death while delivering food, his parents received him in Mexico to bury him in his hometown. There, where the man wanted to return with Ramirez to grow old with her, his remains rested.»

Deja un comentario